Interview with Professor Zulfiqar Bhutta – Minimizing nutritional gaps in the continuum of maternal and child health

Professor Zulfiqar Bhutta

Robert Harding Chair in Global Child Health and Policy

Co-Director, SickKids Centre for Global Child Health

Senior Scientist, Research Institute

The Hospital for Sick Children

Professor, Department of Paediatrics, Nutritional Sciences and Public Health

University of Toronto Founding Director

Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health

The Aga Khan University, South Central Asia and East Africa

- What are the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for maternal and child health?

- What are the current issues in maternal and child health in developed and developing countries?

- What are the evidence-based preconception and antenatal nutritional recommendations for improving birth outcomes (eg, reducing preterm birth, achieving normal birth weight)?

- What are the evidence-based nutritional interventions for improving infant health?

- Summary and take home messages

ZB: Professor Zulfiqar Bhutta

What are the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for maternal and child health?

ZB: In the year 2000, 189 countries collaborated to set eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) with the aim of reducing global extreme poverty, and by 2015 child mortality and maternal mortality ratios had dropped by approximately 50%.1-3

However, poverty and mortality due to severe malnourishment still exist, so 17 SDGs, or ‘Global Goals’, for 2030 were set to build on the achievements of the MDGs and further address the underlying determinants of poverty through4-6:

- Sustainable development

- Improving nutrition

- Achieving food security

- Ensuring healthy lives

- Promoting wellbeing

The SDGs also aim to address the root causes of poverty and the universal need for development for all people,4 including previously neglected groups who were not included in previous maternal health programmes, such as adolescent girls, to cover the continuum from preconception to newborn.

What are the current issues in maternal and child health in developed and developing countries?

ZB: Although worldwide child mortality has been reduced significantly in the last two decades, there are still close to 159 million children under 5 years who have stunted growth, and 41 million who are overweight, while in 2010 alone more than 32 million infants were born small for their gestational age (SGA), and as a result of nutritional deficiencies have a high risk of impaired cognitive development.7-9 Maternal and child health exist on a continuum, where preconception and maternal health considerably affect birth outcomes, as well as infant and child health.10-12 In addition, while malnutrition is more common in the developing world, maternal obesity is also increasing in both developed and developing countries, and both conditions are associated with micronutrient deficiency.7,10,13

Maternal and child health exist on a continuum, where preconception and maternal health considerably affect birth outcomes, as well as infant and child health. 10-12

What are the evidence-based preconception and antenatal nutritional recommendations for improving birth outcomes (eg, reducing preterm birth, achieving normal birth weight)?

ZB: Undernutrition is a key risk factor for still births, SGA and low−birth-weight infants, and accounts for at least one-fifth of maternal deaths.10,14

Promoting improvements in diet and exercise in a sustainable manner

Pre-pregnancy obesity has been linked to conditions such as pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus, but as weight loss is not recommended during gestation, it is important to optimize weight before conception and understand how to manage gestational weight gain.10,13 Therefore, women should aim to exercise regularly, and optimize nutrition intake and weight, before pregnancy.10,13

Food provision and balanced energy/protein supplementation

Food provision and balanced energy/protein supplementation are well-established strategies in malnourished women to improve birth outcomes, as are maternal education and optimal birth spacing of 18–24 months between pregnancies, to avoid nutritional depletion syndrome and improve food security.10,11,15

Dietary diversification

It is important to ensure that diets contain a balance of carbohydrates and fat, and include foods that are rich in micronutrients such as fruits and vegetables.10,11

Micronutrient supplementation

Micronutrient deficiency is prevalent in both underweight and obese populations and is linked to pregnancy outcomes.10,11,13,16

- Folic acid helps prevent birth defects, specifically neural tube defects; however, its use is still largely restricted to the prenatal period, and a global strategy for improving awareness and use of folic acid supplements in all women of child-bearing age is needed.10,11

- Iron supplementation can protect against low birth weight; however, approximately 40% of women worldwide still have anaemia during the preconception period.10 Strategies, including iron fortification of food and co-administering supplements with other interventions, such as intermittent deworming, can improve the iron status of women of child-bearing age.10 Evidence also suggests a possible benefit for at-risk populations in replacing iron-folate supplementation with multiple micronutrient supplementation in pregnancy.11

- Calcium and zinc deficiencies have been linked to adverse birth outcomes and maternal complications.10,11,16 Supplementation during pregnancy has been found to improve maternal and newborn health.10

What are the evidence-based nutritional interventions for improving infant health?

ZB: Many of the factors affecting outcomes in newborns, such as undernutrition, are related to maternal health, reinforcing the importance of interventions to improve preconception and prenatal health.11

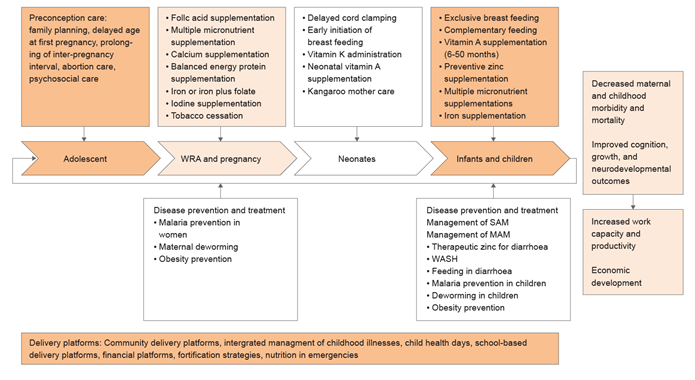

Undernutrition accounts for approximately 45% of mortality in children aged <5 years worldwide,7,17 with approximately 44% of these deaths occurring during the newborn period.12 Therefore, considerable gains can be achieved by treating malnourished children with appropriate interventions (Figure), including11:

- Promoting and supporting exclusive breastfeeding.11,17

- Complementary feeding (introducing nutrient-rich food from 6 months of age, in addition to breastfeeding) and diet diversity.11

- Micronutrient supplementation in children, especially in areas of poverty and in cases of severe acute malnutrition.11,17

- Preventive zinc and vitamin A supplementation in populations at risk of deficiency to reduce the risk of diarrhoea-related mortality.11

Figure: Proposed framework for maternal and child health interventions11

MAM, moderate acute malnutrition; SAM, severe acute malnutrition; WASH; water, sanitation, and hygiene; WRA; women of reproductive age

Many of the factors affecting outcomes in newborns, such as undernutrition, are related to maternal health, reinforcing the importance of interventions to improve preconception and prenatal health

Summary and take home messages:Malnutrition is not inevitable and can be addressed within our lifetime.7 Globally, the number of overweight children under 5 years of age continues to rise and, in terms of the number of people affected, is responsible for a comparable global disease burden as other forms of malnutrition, such as wasting.7

As undernutrition limits child development, and is a significant contributor to maternal and child mortality, these issues must be addressed across generations at community, national, and global levels.1,7,10,11,18 |

WYE-EM-212-SEP-16

Reference

- Unicef. Millennium Development Goals (MDG) monitoring. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/statistics/index_24304.html. Accessed 2 August 2016.

- United Nations. Millennium Development Goal 4: Reduce Child Mortality. Available at: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/childhealth.shtml. Accessed 6 July 2016.

- United Nations. Millennium Development Goal 5: Improve Maternal Health. Available at: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/maternal.shtml. Accessed 6 July 2016.

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Available at: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sdgoverview/post-2015-development-agenda.html. Accessed 6 July 2016.

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 2. Available at: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sdgoverview/post-2015-development-agenda/goal-2.html. Accessed 2 August 2016.

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 3. Available at: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/. Accessed 2 August 2016.

- International Food Policy Research Institute. Global Nutrition Report 2016: From Promise to Impact: Ending Malnutrition by 2030. Washington, DC. Available at: http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/130354/filename/130565.pdf. Accessed 8 July 2016.

- Grantham-McGregor S, et al. Lancet 2007;369:60-70.

- Lee A, et al. Lancet Glob Health 2013;1:e26-e36.

- Dean S, et al. Reprod Health 2014;11(Suppl 3):S3.

- Bhutta Z, et al. Lancet 2013;382:452-477.

- Austin A, et al. Reprod Health 2014;11(Suppl 2):S1.

- Cetin I, et al. J Pediatr Neonat Individ Med 2015;4:e040220.

- Black R, et al. Lancet 2008;371:243-260.

- Salam R, et al. Ann Nutr Metab 2014;65:4-12.

- Black R, et al. Lancet 2013;382:427-451.

- Salam R, et al. J Nutr 2015;145:1116S-1122S.

- Walker S, et al. Lancet 2007;369:145-157.

If you liked this post you may also like