Interview with Professor Ting Fan Leung - Current Approach in the Management of Paediatric Food Allergies

We recently had the privilege to speak with Professor Ting-fan Leung, a paediatric allergist from The Chinese University of Hong Kong and Prince of Wales Hospital. During the interview, Professor Leung discussed the latest developments on the diagnosis, investigation and treatment of childhood food allergies. Highlights from this interview are presented here.

- Advice on how to diagnose food allergies

- Guidance on the management of food allergies and useful tips

Professor Ting-fan LEUNG

Department of Paediatrics

The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Prince of Wales Hospital

Shatin, Hong Kong

INTRODUCTION

Food allergy remains a health concern in many developed nations.1 In Hong Kong, a community-based questionnaire study showed that the rate of parent-reported adverse food reactions in children aged 2 to 7 years was 8.1% in 2007/2008.2

Depending on the allergic mechanism, children may experience immediate or delayed onset of symptoms. Regardless, the potentially fatal nature of certain food allergies can sometimes cause severe parental anxiety. Consequently, this may cause avoidance of single or entire food groups. Such actions are often unnecessary as food-induced adverse reactions can be attributed to non-allergic mechanisms, such as food intolerance, acute gastroenteritis and food poisoning.3 Therefore, a correct diagnosis is the first and most important step towards managing paediatric food allergies.

A correct diagnosis is the first and most important step

towards managing paediatric food allergies

- WHAT ARE FOOD ALLERGIES?

- WHAT CAUSES FOOD ALLERGIES?

- HOW ARE FOOD ALLERGIES DIAGNOSED?

- HOW SHOULD FOOD ALLERGIES BE MANAGED?

- USEFUL TIPS FOR HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS

- FINAL THOUGHTS

WHAT ARE FOOD ALLERGIES?

There are three broad mechanisms of food allergies – IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated (cell-mediated) and mixed type.3 IgE-mediated reactions develop rapidly (< 2 hours) and involve the crosslinking of IgE molecules adhered on the surface of mast cells and basophils by allergens. Non-IgE-mediated reactions take longer to develop (2 to 48 hours) as they require the activation of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. It is also possible for a child to possess both IgE- and non-IgE-mediated food allergies (mixed type).3 Listed in Table 1 are some of the most common hypersensitivity disorders.

IgE-mediated reactions develop rapidly (< 2 hours)…while non-IgE-mediated reactions take longer to develop (2 to 48 hours)

Table 1. Food hypersensitivity disorders

|

Mechanism |

Cutaneous |

Gastrointestinal |

Respiratory |

Systemic |

|

IgE |

Urticaria, angioedema, flushing |

Oral allergy syndrome, gastrointestinal anaphylaxis |

Acute rhinoconjunctivitis, bronchospasm, laryngeal oedema |

Hypotension, anaphylactic shock |

|

Non-IgE |

Contact dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis |

Food protein-induced enterocolitis and enteropathy, coeliac disease |

Food-induced pulmonary haemosiderosis (Heiner Syndrome) |

|

|

Mixed |

Atopic dermatitis(eczema) |

Allergic eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroenteritis |

Asthma |

|

WHAT CAUSES FOOD ALLERGIES?

Food allergens can be divided into two classes based on their biochemical properties. Class I allergens are water-soluble glycoproteins (10-70 kDa) that are resistant to heat, acid and proteases.4 Examples of foods that fall within this class are egg, cow's milk, peanut, and fish.3 Class II allergens are heat-labile and bear structural homology to tree and weed-derived pollens (Table 2).5

Table 2. Class II food allergens6

|

Source of pollen |

Foods with structural homology |

|

Birch |

Fruits: Apple, peach, plum, nectarine, cherry, pear Nuts: Almond, hazelnut Vegetables: Carrot, celery, raw potato |

|

Grass |

Fruits: Melon, kiwi, peach Vegetables: Tomato |

|

Mugwort |

Vegetables: Carrot, celery Spices: Caraway seeds, parsley, coriander, anise seeds, fennel seeds |

|

Ragweed |

Fruits: Melon (watermelon, cantaloupe and honeydew), banana Vegetables: Tomato, cucumber |

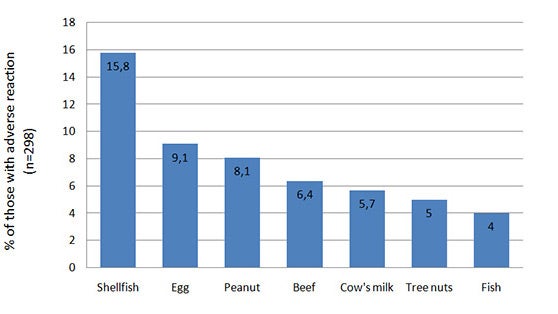

A survey of children aged 2 to 7 years living in Hong Kong to ascertain the occurrence and clinical spectrum of adverse food reactions showed that the leading causes of such problem were shellfish, egg, peanut, beef, cow's milk and tree nuts (Figure 1).2

Figure 1. Prevalence of the most common parent-reported adverse food reactions2

COW'S MILK PROTEIN ALLERGYMilk is one of the most common food allergies encountered in the first 3 years of life.7 It is also the fourth most prevalent food allergy among children in Hong Kong after egg, peanut and shellfish.2 Although the majority of children outgrow their milk allergy by the age of 3 years7, avoidance of cow's milk protein (CMP) during these first few years of life can be particularly challenging. This is because milk and dairy products typically form a major proportion of infant and toddler diets. |

HOW ARE FOOD ALLERGIES DIAGNOSED?

Patient history

The first and most crucial step towards identifying a food allergy is to formulate a diagnostic plan based on a child's medical history. Parents are often encouraged to keep a food journal that consists of the following:3

a) Suspected food allergen

b) Quantity of food ingested

c) Amount of time between ingestion and adverse reaction

d) Whether a similar adverse reaction had occurred previously

e) Last occurrence of an adverse reaction

The medical history regarding frequency, nature and severity of an adverse food reaction can often be used in conjunction with food-specific IgE testing to rule out food allergy.

Food-specific IgE testing

The two most commonly used methods for detecting the presence of specific IgEs in food allergic patients are the skin prick (SPT)12 and radioallergosorbent (RAST) tests13 (Table 3). There is a common misconception that any positive result from these tests is indicative of true food allergies. In fact, SPT and RAST are much more useful in excluding rather than diagnosing food allergies.

SPT and RAST are more useful in excluding rather than diagnosing food allergies

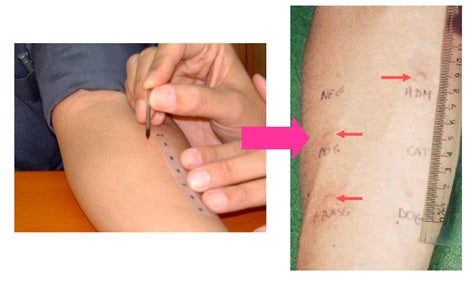

Skin prick test requires the introduction of purified food allergen extracts either percutaneously or intracutaneously (Figure 2). Allergens that induce the appearance of a wheal ≥ 3mm greater than the negative control (saline or diluent) are commonly reported to be positive.3

Figure 2. Skin prick test

RAST measures the concentration of allergen-specific IgE in the serum of a patient. The principle is that the greater the amount of allergen-specific IgE (higher score), the higher the probability that a patient is allergic to that food.14

In general, SPT and RAST have similar sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing sensitisation to food allergens. Due to the low sensitivity of RAST, a fluorescent enzyme immunoassay (CAP-FEIA) was developed. Based on the same principle as RAST, CAP-FEIA has been optimised to detect even low levels of allergen-specific IgE. In a prospective study, CAP-FEIA was found to have a positive predictive value (PPV) of greater than 90% for egg, peanut and milk allergies but was less effective in predicting fish allergy.15

While specific IgE testing is useful for ruling out a food allergy, a positive result cannot form the only basis for a food allergy diagnosis. Presence of allergen-specific IgE indicates food sensitisation that does not always translate into clinical reactivity upon ingestion of such food.16 Results of specific IgE testing should always be interpreted in the light of clinical history. For example, food allergy can be diagnosed in patients with even weakly positive SPT or RAST to a certain food who experience symptoms typical of IgE-mediated reactions such as hives, angioedema and wheeze within two hours of ingestion of that food. On the other hand, cross-reactivity between food proteins may mask the true identity of the causative allergen.13 Therefore, in an IgE-positive patient with an absent or doubtful food-related history, the next diagnostic step is to perform a supervised and preferably double-blind challenge with the suspected food to confirm whether the patient develops allergic symptoms following food ingestion.

Table 3. IgE tests3

|

Specific IgE Test |

Pros and Cons |

|

Skin Prick Test

|

Pros:

Cons:

|

|

Radioallergosorbent Test

|

Pros:

Cons:

|

Oral challenge and elimination diet

Foods not expected to induce a severe allergic reaction can be screened in an open, single-blind or double-blind and placebo-controlled food challenge, the last option being considered as the gold standard for food allergy diagnosis.12 An additional problem regarding the application of SPT and RAST is that they are only useful in detecting IgE-mediated food allergy. As stated above, a significant proportion of food-related allergic reactions are mediated by non-IgE-mediated mechanisms. In such patients or those with inconclusive results from an oral food challenge, they are advised to adopt an elimination diet which typically consists of the following steps:

- Exclude the suspected food(s) from their diet for 7-14 days (for IgE-mediated reactions) or longer (eg, up to 6-8 weeks for non-IgE-mediated or mixed reactions)

- Avoid medications that can mitigate or reduce the symptoms of an allergic reaction (eg, antihistamines)

Suspected foods are then reintroduced during an open feeding session to confirm if they elicit symptoms such as eczematous rash and gastrointestinal discomfort. Such allergic symptoms typically reappear within 48-72 hours following food re-challenge. In some circumstances, open feeding sessions maybe performed at home under the supervision of a responsible and educated caregiver. However, the decision on the preferred food challenge setting needs to be made by the patient's attending allergist.

HOW SHOULD FOOD ALLERGIES BE MANAGED?

After the causative food(s) and nature of the food allergy have been identified, it is imperative to involve patients and their families in the management approaches.

- AVOIDANCE of the causative food(s) is the most commonly prescribed approach. This option requires that the patient and his/her family be educated and committed in avoiding accidental ingestion of the potentially allergenic food(s).

It is important to note that the natural history of different food allergies varies. Most children outgrow their allergy to cow's milk, egg, wheat and soybean by the age of five years. On the other hand, allergies to peanut, tree nuts, shellfish and fish commonly persist into adolescence and even adulthood. Currently, there is no reliable predictor of patients' natural history. However, those with weakly positive results on SPT or RAST at diagnosis were observed to have higher chance in outgrowing their food allergies with time. Serial SPT and/or RAST may thus be necessary to follow the progress of food allergies in the affected patients.

- MEDICATION is an important component of food allergy management, particularly when complete avoidance of a certain food is not possible. Patients with severe food allergy may experience anaphylaxis when they have breathing difficulty or low blood pressure or both.

Adrenaline is the medication of choice for patients who develop anaphylaxis. Many studies have consistently shown that early use of adrenaline was associated with improved outcomes from anaphylaxis. Adrenaline is commercially available as an autoinjector (eg, EpiPen, Anakit, Jext) to be kept at room temperature. This allows patients to carry it with them at all times. At the start of anaphylaxis, patients can self-deliver adrenaline into their anterolateral thigh to halt any severe and life-threatening reaction.

Antihistamines can alleviate oral allergy syndrome and cutaneous features of IgE-mediated allergy such as hives, skin itching and angioedema as well as upper airway symptoms such as rhinorrhea, sneezing and eye discharge. Oral and in severe cases intravenous corticosteroids should also be prescribed to control asthma exacerbations, severe ocular and rhinitic symptoms as well as non-IgE mediated gastrointestinal disorders. Food allergic children with coexisting asthma will benefit from treatment with as-needed inhaled bronchodilators (eg, salbutamol or terbutaline).

In addition to patient education, it is imperative for families with food allergic children to work with allergists in formulating an individualised action plan for severe allergic reactions that consists of a combination of the medications described above. The majority of these families need to be taught on when and how to administer an adrenaline autoinjector. Parents should also communicate such pertinent information to all parties (eg, daycare centre, kindergarten) involved in the care of such patients.

- ORAL AND SUBLINGUAL IMMUNOTHERAPY is a novel treatment option for food allergy.17 A number of studies have been published on this treatment modality for cow's milk, egg, peanut and tree nut allergies. This therapy involves the delivery of food allergens in carefully regulated, escalating doses, with the goal of desensitising patients towards the food allergen. However, this treatment has not been well standardised for routine clinical use at present.

- NOVEL PHARMACOTHERAPY for food allergy include anti-IgE treatment and traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Anti-IgE treatment, currently licensed for severe uncontrolled allergic asthma, works by removing circulating IgE molecules that trigger food allergen-specific immune reactions. A randomised and placebo-controlled clinical trial demonstrated that such treatment increased the threshold of peanut allergens required to induce an allergic reactions, thereby improving the safety of peanut allergic patients.18 Traditional Chinese herbal medicine was shown both in vitro and in vivo to be efficacious in treating food allergies.19 Further studies of these novel approaches are ongoing to better delineate their roles in food allergy treatment.

USEFUL TIPS FOR HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS

- Adverse food reactions can be caused by both allergic and non-allergic conditions, and it is imperative to exclude food intolerance and toxin and infective aetiologies in such patients.

- Food allergies are prevalent in young Hong Kong children, who frequently suffer from comorbidities such as eczema, asthma and allergic rhinitis. The immunological mechanisms leading to food allergies are mediated by IgE (immediate) and/or lymphocytes (delayed).

- There is a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations for food allergies that involve one or more of the cutaneous, gastrointestinal, respiratory and cardiovascular systems. Such allergic symptoms are evident either early (< 2 hours) or delayed (up to 2-3 days) following food ingestion.

- Both SPT and RAST detect the presence of food-specific IgE, which have similar diagnostic performance for detecting food sensitisation. It is pertinent to consider patients' clinical history when interpreting these allergy tests. Their high specificity implies that food allergies may be excluded among patients with negative results. The probability of true food allergies increases with increasing size of wheal for SPT and allergen-specific IgE concentration for RAST.

- Supervised food challenges offer the definitive way to diagnose food allergies, but such patients may need to eliminate the suspicious foods from diet for several weeks before food re-ingestion.

- Strict food avoidance and pharmacotherapy are the main treatments for food allergies. Adrenaline is the first-line drug for severe respiratory and/or cardiovascular symptoms. It is important to help such families to formulate an action plan for managing allergic reactions that range from mild isolated urticaria to life-threatening anaphylaxis.

FINAL THOUGHTS

In a society like Hong Kong where eating holds social, relational and emotional importance, the topic of food allergies among children is close to the hearts of many parents. Accurate and timely diagnoses coupled with careful management and reassurance can help families with food allergic children to appropriately and effectively deal with this potentially life-threatening condition.

WYE-EM-127-JUL-13

Reference

- Sicherer SH. Epidemiology of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127(3): 594-602.

- Leung TF et al. Parent-reported adverse food reactions in Hong Kong Chinese pre-schoolers: epidemiology, clinical spectrum and risk factors. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2009; 20(4): 339-46.

- Sampson HA. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 111(2 Suppl): S540-7.

- Sampson HA. Food allergy. Part 1: immunopathogenesis and clinical disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 103(5 Pt 1): 717-28.

- Breiteneder H and Ebner C. Molecular and biochemical classification of plant-derived food allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 106(1 Pt 1):27-36.

- Han Y et al. Food allergy. Korean J Pediatr 2012; 55(5): 153-58.

- Venter C et al. Prevalence and cumulative incidence of food hypersensitivity in the first 3 years of life. Allergy 2008; 63(3): 354-9.

- Kneepkens CM and Meijer Y. Clinical practice. Diagnosis and treatment of cow's milk allergy. Eur J Pediatr 2009; 168(8): 891-6.

- Zeiger RS et al. Soy allergy in infants and children with IgE-associated cow's milk allergy. J Pediatr 1999; 134(5): 614-22.

- Klemola T et al. Allergy to soy formula and to extensively hydrolyzed whey formula in infants with cow's milk allergy: a prospective, randomized study with a follow-up to the age of 2 years. J Pediatr 2002; 140(2): 219-24.

- Hill DJ et al. The efficacy of amino acid-based formulas in relieving the symptoms of cow's milk allergy: a systematic review. Clin Exp Allergy 2007; 37(6): 808-22.

- Sampson HA. Food allergy. Part 2: diagnosis and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 103(6): 981-9.

- Hamilton RG and Adkinson Jr NF. Clinical laboratory assessment of IgE-dependent hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 111(2 Suppl): S687-S701.

- Celik-Bilgili S et al. The predictive value of specific immunoglobulin E levels in serum for the outcome of oral food challenges. Clin Exp Allergy 2005; 35(3): 268-73.

- Sampson HA. Utility of food-specific IgE concentrations in predicting symptomatic food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 107(5): 891-6.

- Cox L et al. Pearls and pitfalls of allergy diagnostic testing: report from the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Specific IgE Test Task Force. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008; 101(6): 580-92.

- Kulis M and Wesley Burks A. Oral immunotherapy for food allergy: Clinical and preclinical studies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2013; 65(6): 774-81.

- Leung DY et al. Effect of anti-IgE therapy in patients with peanut allergy. N Engl J Med 2003; 348(11): 986-93.

- Li XM. Traditional Chinese herbal remedies for asthma and food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120(1): 25-31.

If you liked this post you may also like

Factors influencing brain development in early life